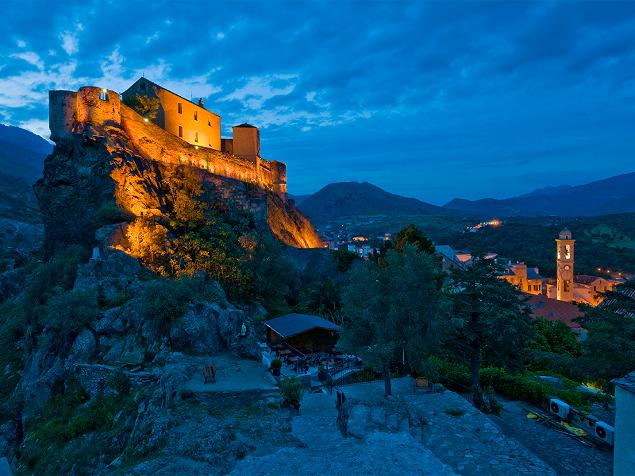

Corsica: Napoleon’s Soulful Island Home

Two

hundred years after Napoleon Bonaparte suffered his final military

defeat, Corsica, his birthplace, stubbornly resists its own cultural

Waterloo. Though this Mediterranean island has deep, historic ties to

Italy and has been part of France since 1769, its 300,000 inhabitants

retain a fierce pride in their own unique culture, including the

proverb-rich Corsican tongue. But to keep that birthright vibrant in the

face of tourism and its homogenizing effects, their battle remains

constant.

Fortunately,

most of the island’s three million annual visitors come for the

undeniable pleasures of the coast or for the thrill of visiting historic

La Maison Bonaparte, in the city of Ajaccio. All of which leaves the

island’s mountainous interior largely untouched. “Go inland and you will

find the soul of Corsica,” advises Jean-Sébastien Orsini, director of a

traditional Corsican polyphonic choir in the foothill town of

Calanzana.

Olive groves and quiet villages dot the slopes and isolated valleys of the interior, vast swaths of which are protected by the Parc Naturel Régionale de Corse, which covers more than 40 percent of the island. Hiking trails lace forests of oak and pine. In the villages here, you encounter Corsicans who still feel passionately the adage “Una lingua si cheta, un populu si more—A language is silenced, a people die.”

Olive groves and quiet villages dot the slopes and isolated valleys of the interior, vast swaths of which are protected by the Parc Naturel Régionale de Corse, which covers more than 40 percent of the island. Hiking trails lace forests of oak and pine. In the villages here, you encounter Corsicans who still feel passionately the adage “Una lingua si cheta, un populu si more—A language is silenced, a people die.”

Koyasan, Japan: Let There Be Enlightenment

The

austere heart of Japanese Buddhism beats loudly at Koyasan, a monastic

complex that lies two hours by train south of Osaka. Koyasan marks its

1,200th anniversary in 2015.

Established by revered scholar-monk Kobo Daishi in 816 as the headquarters for his Shingon school of Esoteric Buddhism, Koyasan remains one of Japan’s most pristine and sacred sites, manifesting a masculine side of Japan worlds away from the hostesses and Hello Kittys of Kyoto.

Established by revered scholar-monk Kobo Daishi in 816 as the headquarters for his Shingon school of Esoteric Buddhism, Koyasan remains one of Japan’s most pristine and sacred sites, manifesting a masculine side of Japan worlds away from the hostesses and Hello Kittys of Kyoto.

“Koyasan

is purity,” says a monk after a crack-of-dawn fire ceremony, where a

priest burns wooden wish-tablets to the boom of a taiko drum and the

sprinkling of herbs and oils on high-leaping flames. Staying in one of

the temples that welcome guests here opens a portal onto everyday

monastic life. Waking to enshrouding mists, visitors are invited to join

morning chants swirled by cymbals, gongs, and incense. At night,

no-nonsense monks who began the day hand-scrubbing wooden hallways

roughly plop vegetarian feasts in front of visitors.

Kobo Daishi is believed to live here still, sitting in eternal meditation in an elaborate mausoleum, and through the centuries, Japan’s most rich and powerful have built palatial sepulchers here as well. At night, a ghostly lantern-lit trail winds among the moss-covered stones deep into the mystery and majesty of ancient Japan. —Don George

Kobo Daishi is believed to live here still, sitting in eternal meditation in an elaborate mausoleum, and through the centuries, Japan’s most rich and powerful have built palatial sepulchers here as well. At night, a ghostly lantern-lit trail winds among the moss-covered stones deep into the mystery and majesty of ancient Japan. —Don George

Tunis, Tunisia: New Day in North Africa

Byrsa

Hill, in Tunis’s upmarket suburb of Carthage, makes a dizzying aerie to

watch the sun set into the bay. The vantage point might be the Light

Bar at the decidedly 21st-century Villa Didon, but Phoenician streets

lay deep beneath and, down on the waters’ edge, the scalloped foreshore

traces a Roman naval port. Inland, the coils of the ancient medina and

the colonial grid of the early 20th century French city tell other

chapters of Tunis’s story of conquest, resistance, flux, and

assimilation, from mythic Dido to the Jasmine Revolution of 2011.

The

city’s layered charms are something that many pre-revolution visitors

missed entirely, on their way to the Sahara or the Mediterranean beach

resorts of Hammamet and Sousse. These sun-holiday tribes all but

abandoned Tunisia after 2011, but with a relaxation of most travel

warnings to the country, a new breed of traveler has replaced them. They

come to discover Tunis’s past, yes, and now also its cultural energy,

what Ahmed Loubiri, the organizer of international electronic music

festival Ephemere, sees as a widespread “urge to be creative.” Loubiri

says this ranges from “random jam sessions in garages and coffee shops

to humongous festivals.” Galleries such as Selma Feriani and Hope

Contemporary continue to thrive in the neighborhoods of La Marsa and

Sidi Bou Said, and Tunis’s antiquities museum, the Bardo, has reopened

with an ambitious new wing.

“It’s a Tunisian habit to know how to receive guests. We get back as much as we give,” says Marouane ben Miled, who runs La Chambre Bleue, a medina B&B, suggesting that this fresh popularity might also mark the beginning of a fertile conversation.

“It’s a Tunisian habit to know how to receive guests. We get back as much as we give,” says Marouane ben Miled, who runs La Chambre Bleue, a medina B&B, suggesting that this fresh popularity might also mark the beginning of a fertile conversation.

Sark, Channel Islands: Tradition’s Last Stand

In

Sark, time flows like molasses. Sarkees will mark the 450th anniversary

of feudalism in 2015; the tiny Channel Island off the coast of Normandy

abolished the medieval form of governance in 2008. But old ways linger:

The two banks have no ATMs; the unpaved roads lack street lights; cars

are banned. Signposts usefully give distances in walking minutes, for in

this unhurried place ambling is what one does—or cycling, or riding in a

horse-drawn carriage. Wander country roads bordered by fieldstone walls

and storybook cottages, past foxgloves and bluebells and 600 other

kinds of wildflowers, taking note of butterflies, seabirds, Guernsey

cows. Destination? Perhaps the sea caves of Gouliot Headland, to find

anemones. Or La Marguerite Cottage, to buy duck eggs from Sue Adams’s

streetside honor box. Or Venus Pool, for a swim at low-tide. Or

especially La Coupee, to walk the skinny track atop an isthmus 300 feet

above the sea.

A visitor’s daytime choices abound. But late at night, there’s just one: the sky. Sark is the first island certified by the International Dark-Sky Association. Time may have swept feudalism aside. The stars are timeless. — Peter Johansen

A good Muslim ruler was expected to be an expert with the pen as well as the sword; the city’s founder, Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah, is credited with the first published anthology of Urdu poetry. The later ruling dynasty, the Nizams, provided patronage to poets within their court. Attend a mushaira (poetry symposium) for a good introduction to the city’s literary legacy. There’s also the Hyderabad Literary Festival in January, followed by February’s Deccan Festival, during which the most passionate performances involve qawwali, an 800-year-old form of Sufi music. Another evocative setting to witness qawwali is Chowmahalla Palace, the recently restored residence of the Nizams. “Dakhan—Hyderabad—is the diamond, the world is the ring,” says historian Narendra Luther, quoting the court poet Mulla Vajahi. “The ring’s splendor lies in the diamond.” —Simar Preet Kaur

A visitor’s daytime choices abound. But late at night, there’s just one: the sky. Sark is the first island certified by the International Dark-Sky Association. Time may have swept feudalism aside. The stars are timeless. — Peter Johansen

Hyderabad, India: A Diamond Is Forever

Stories

of Hyderabad’s poetic past weave amid strings of programming code in

this southeastern India city that was home to one of the richest men in

the world, Mir Osman Ali Khan, the last ruling nizam of Hyderabad. Now a

seedbed for many global IT brands, Cyberabad (as it’s dubbed) is where

you can hear the muezzin’s call above the traffic din generated by aging

Urdu scholars and young software engineers alike. Here, ancient

boulders guard the peripheries of HITEC City, while new rooftop bars hem

in lakes and gardens. The opulent Taj Falaknuma Palace hotel perches

atop a hill overlooking the Old City, where Irani cafés thrive alongside

fifth-generation pearl merchants and the finest fountain pen makers.

Prone to exaggeration, the Hyderabadis’ conversations within these cafés

often linger over three cups of chai and four hours.

A good Muslim ruler was expected to be an expert with the pen as well as the sword; the city’s founder, Mohammed Quli Qutb Shah, is credited with the first published anthology of Urdu poetry. The later ruling dynasty, the Nizams, provided patronage to poets within their court. Attend a mushaira (poetry symposium) for a good introduction to the city’s literary legacy. There’s also the Hyderabad Literary Festival in January, followed by February’s Deccan Festival, during which the most passionate performances involve qawwali, an 800-year-old form of Sufi music. Another evocative setting to witness qawwali is Chowmahalla Palace, the recently restored residence of the Nizams. “Dakhan—Hyderabad—is the diamond, the world is the ring,” says historian Narendra Luther, quoting the court poet Mulla Vajahi. “The ring’s splendor lies in the diamond.” —Simar Preet Kaur